Private piece, no connection to my employer. WARNING: contains distressing scenes, ie exhumation and embalming

When you’re alone in the cinema, at a midnight showing, it’s okay to cry as much as you need to, as I did tonight. Only when you laugh do you miss having nobody else around.

There’s some other advice about where to shed tears in The Last Dance (破·地獄) the Hong Kong film about a funeral director and a priest released this month in the UK, as well as in the Chinese territory itself. When you are standing by a bier, says one of the characters, “Don’t let tears touch the departed – she won’t want to leave.”

Just reading this quote (seamlessly subtitled into English from Cantonese), contained in the wonderful script of this intricate, subtle, tender, impeccably acted film, my eyes well up again. Having lost both my parents over the past five years, one just before the Covid pandemic, the other not long after, I am as receptive as any to a film about how we say the great goodbye. Mind you, that wasn’t why I went to see The Last Dance.

I wanted to see a film billed as an exploration of Taoist funeral rites in modern Hong Kong. The subject has intrigued me since I spent four months working in Singapore this year. On my walks through the concrete jungle of the stacked city-state, I would see paper gifts for the dead being burnt in the fire bins which seem to stand outside every apartment building. Sometimes I would pass actual funeral ceremonies on the “void decks” – the open spaces under the buildings – with masked dancers performing before solemn congregations.

A Singaporean taxi driver told me once that Taoist funerals on the island (where ethnic Chinese make up the majority of local residents) cost much more than those of Buddhists because of the elaborate rites involved, and this, he suggested, was one reason why people were drifting towards Buddhism. I could see how financial cost might be a factor, as it was to a degree in the rise of Protestantism over Roman Catholicism in northern Europe during the Reformation. In fact there is a sub-plot in The Last Dance involving a conflict over someone changing their religion – from Taoism to Roman Catholicism – to try to gain school admission for their child. While such a situation is not unusual one feels that the theme of one part of Hong Kong’s identity being eroded may also be symbolic of a broader change of life for the former British colony. Some things must remain unspoken, one feels, for such films to be made in China.

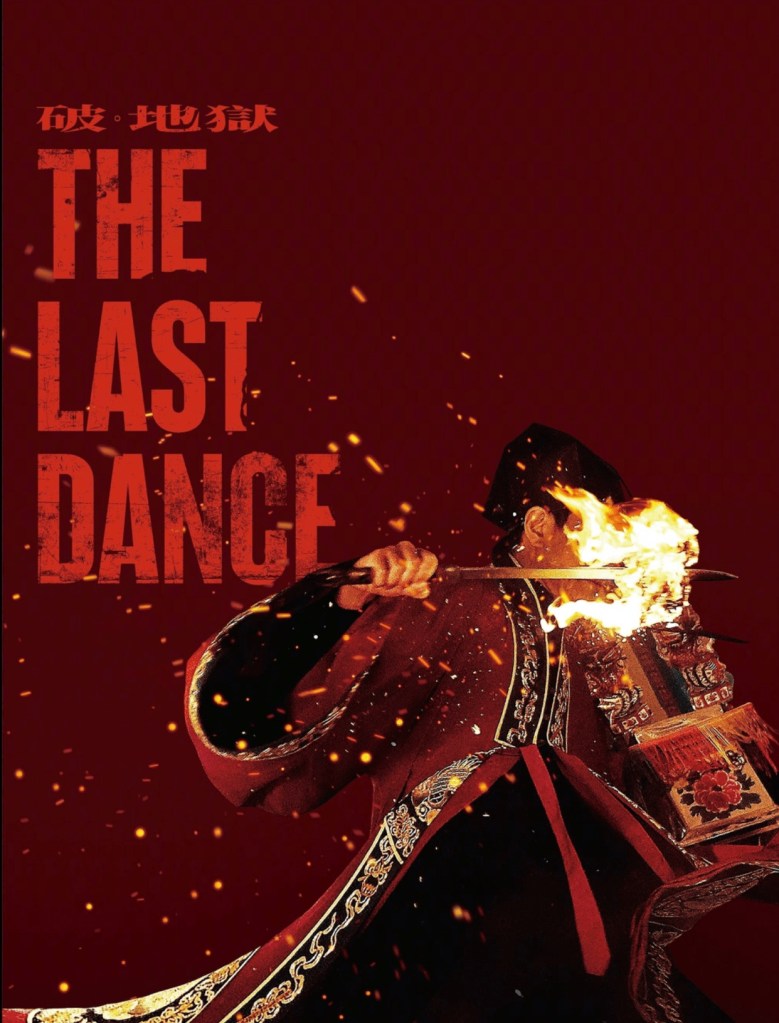

You do learn much about the Taoist way of death in this film and the dramatic, full-dervish ceremony of “breaking Hell’s gates”, when the newly dead are symbolically freed from Hell to take the path of reincarnation, ties the plot together.

However, as one character says, “living can be Hell” too, and it’s as important to “liberate the living” as the dead. Another strong theme here is the inferior place of women in a patriarchal society, where menstrual blood is despised and feared by religious zealots. A husband may regard his wife as his property in death as in life, controlling who may come to mourn her death. There is bewilderment among an older generation at why some women would live together with men without marrying. For other single women, sex is a loveless affair with a married man, with no commitment. Michelle Wai is outstanding as a paramedic, grappling with the dying in her ambulance, but all the female roles here are memorable.

The pandemic is initially a plot device to explain why 50-something wedding planner Dominic (Dayo Wong) is struggling, post-Covid, under crushing debt after the collapse of his business. He takes up the offer of a job as a funeral director to replace his Uncle Ming (Paul Chun), on the basis that some of the needs of the newly dead are not unlike those of the newly wed.

In one of the funnier scenes (I did laugh in places, remember), Dominic is told: “You say money means nothing to you? You light up at the sight of money!” In another scene, the emigration prospects of a younger character called Ben (Park Hon Chu), who struggled at school before being pressed into the priesthood to the mockery of his friends, are dismissed like this: “What’s he going to do in Melbourne. He can’t speak English. He can’t speak Chinese!”

Dominic seems to “light up” most of all at one grief-stricken client who is ready to “spare no expense” for her dead child. In fact the work that follows is so harrowing it changes his character and his dealings with the rigidly traditional priest, Master Man (Michael Hui), who came with the business when Uncle Ming stepped down.

Just as the pandemic still casts a shadow over Hong Kong in the film, where medical staff grown callous call corpses “fish”, Death itself is never far away. The director, Anselm Chan, presents it in all its shocking ugliness in an early scene where Uncle Ming exhumes and scrapes clean the skeleton of a loved one for a family, who watch reverently at the graveside. While there are other upsetting scenes later, the main business of the film appears to be about how best to respond emotionally to that fatal day when you and another person find yourselves “far apart”, to quote an old song which Dominic and Master Man like to sing together.

Life, according to Master Man, philosophical when he is not warring with his children, is a bus ride. When you reach the terminus, you have to get off. The funeral director and the priest are just there to help you off – in the priest’s case, to help you make your connection. Meantime, he says, get chatting to the other passengers and make the best of the ride.