Impressions of Singaporean culture.

Private piece, no connection to my employer, BBC News.

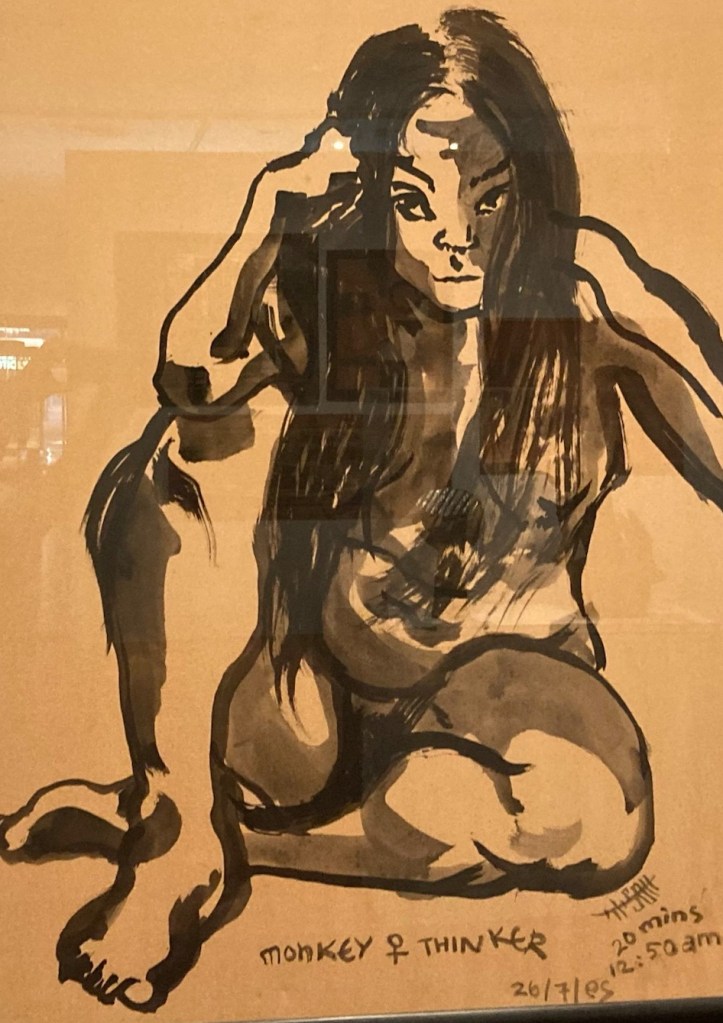

She is in her birthday suit like the macaques near the causeway on St John’s Island but she is not looking for food or fun as she props her long-haired head on her knuckles.

Great eyes lock on with one question, What are you going to do about it? She is her own woman and always will be while her picture – Monkey♀Thinker by Ho Soon Yeen – hangs on the wall of the National University of Singapore Museum. People of any kind can come in and see her, the place is free, but when she is not stealing their breath away she may just pick their bags of prejudices about her island, her continent, her gender. Art exacts its own price, sometimes fast as a monkey, other times slow as wisdom dawning.

A macaque-like figure squats on a chair two floors up, lonely as a cloud, a laptop for its fruit.

Centimetres away in the Sun-bleached street, some migrant labourers sleep out the heat of the Singapore day. Others sink down in the back of a tiny Toyota truck ferrying them between work and hostel.

The glimpses of a city of perpetual construction smoulder in the cool, collected indoors of the museum in the sketches of Goi Yong Chern, new pieces of the culture of a continent which once had its own civilisation with no help from the West, thanks very much.

A world that, in China, fought its own wars, time curving back along the blade of a bronze halberd from the 5th Century BC, when the Art Of War was being written, that drank its own wine, time trickling out of a goose-head jug from the 3rd Century BC, that delighted in fishes in a pool of deep time on the bottom of a green-glazed dish from the 14th Century AD, time lapping at the glass in a museum which preserves Asia’s past and curates Singapore’s present.

High above the reek of the mangrove swamp at low tide, a few metres behind the roar and sting of the waterfalling rain, on the steps of the birdwatching tower, the cheery technician uses his weekend hours to read his way across China, his father’s land, with a book written in Mandarin.

His smartphone drops and clatters on to the wooden steps when he moves. The books of Jia Pingwa could be in his phone too but he prefers the “savour” of the slightly yellowed pages of the actual book (he cannot translate the name), with its plain cover, in his hands. He also likes one Western book, he says as the rain makes an island of the bird tower – Adrift: Seventy-six Days Lost at Sea.

At the edge of the water that brought the Chinese to this place, down by the port, Singapore comes clothed in a glossy book jacket, inscribed in the language of a different wandering people, the English.

On the ground floor of the massive warehouse, crammed into one half of the tiny space that is the Epigram Coffee Bookshop, where a sign gives fair warning about the alarming possibilities inherent in a freestanding book case, a friendly trio of authors scythe through their works for a hungry audience.

In the cafe half, a young woman serves black coffee, the sacred scent impregnating books on cooking, snaking up the sheer face of a majestic album on high-rise gardens. Idle paws flick through a history of Singapore’s French connections, a local guide to “woke” living and four decades of local art history, each written in impeccable English in the appropriate register, each published independently by Epigram Books. Seize, if not the day, then the book, for if life is short, the insider account of the island’s funeral business also on sale here feels pleasurably long. A full wall of other books beckons like a dazibao but in between huddle the readers and writers so that will have to be another time. “Come back when the books are free, friend,” is the message written on the air.

An exhibition of work by art and design students occupies the other end of the warehouse one afternoon in early May. On a table lie two copies of a little unpublished book written and illustrated by Lim Jie Ru. Called How Far is the Sun? it is a fable for children and former children about the first challenges of life’s journey, painted and written on leaves from the same tree as The Little Prince, created in Singapore but dreamt up in the world all children share.