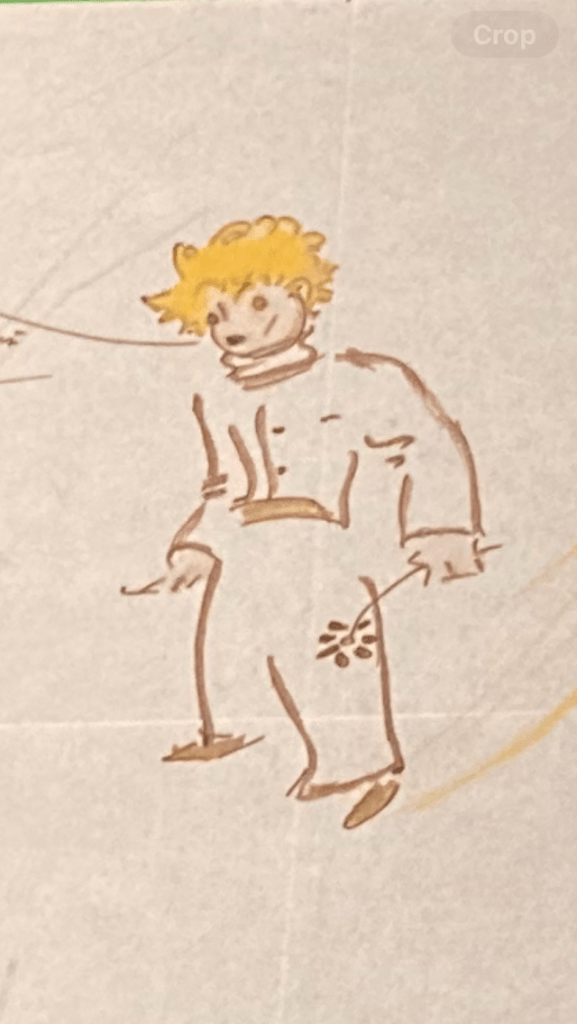

In a room upstairs at the Singapore Alliance Française, photos and souvenirs mark 80 years since the death of Antoine de Saint-Exupéry. “All big people were children first (but few of them remember),” reads the dedication to The Little Prince. In Singapore, where the MRT metro trains teem with little schoolchildren in huge schoolbags on weekday afternoons, and fathers skip with tiny daughters along the interchange walkways at weekends, they remember, maybe even enough for all of us.

The Little Prince, Saint-Exupéry’s last novel, was published on 6 April 1943 while he was living in exile in New York, waiting for his chance to get back into the war.

Ten days before, the Russian composer Sergei Rachmaninov, whose own exile in America, without hope of return, had been so much longer and more bitter, died of illness. His break with Russia during the Revolution in 1917, as much emotional as physical, had left him barely able to compose but a few years before his death he wrote his final piece, Symphonic Dances, a cycle of sorrow and joy that can be heard as a summing-up of his music and life, echoing earlier works.

In the great space of the Esplanade Concert Hall one evening in March, under the baton of Joshua Tan, the Singapore National Youth Orchestra shares Rachmaninov’s journey back to his lost Russia with a new audience, mostly young and almost all as Asian as the musicians themselves. Conductor and orchestra join as one as cultural barriers fall away for an hour between South and North, Asia and Europe, 21st and 20th centuries, past and present, the living and the dead. As the composer once quoted the German poet Heinrich Heine as saying: “What life takes away, music gives back.”

White smoke blows from a bonfire of paper offerings to the new dead on a rainy evening in a street in the suburbs.

On the void deck of an apartment block, as strangers pass on the footpaths outside, two mummers in heroic masks gently dance around a table, where a framed photo of a smiling businesswoman stands, as a congregation of ageing men watch silently in mourning.

In the temple chant the monks.

Through pavement arcades in the old town glide Chinese Opera singers in robes. On the street stage behind them another pair, out of costume and make-up, hold a venerable audience spellbound through the power of their singing alone.

At Chinese New Year, in the yard of the huge Jurong East mall, the spirit of the monkey runs free as young lion dancers with their great dragon and their band visit the stores.

The lions of Armenian Street are more discreet, prowling the tops of doors in the Peranakan Museum where butterflies alight on crockery and textiles from the homes of some of Singapore’s wealthy mixed-race families who prospered in colonial times.

If Asia has a parlour, a quiet, comfortable, intimate, friendly place offering beautiful, homely things to catch the eye and warm the heart, this may be it.