Private piece of travel writing, no connection to my employer

16 September 2023: I remember Paris. Long has it been in hours and kilometres since the steam ascended from the claps of human excrement dotting those Parisian walkways. This morning I navigated around them after squeezing myself out of a coach in the dim and cavernous bus station they call, as sexily as a Siren, Bercy-Seine. Bercy-Seine mon amour – it could be the name of a pre-apocalyptic film. For some among the multitude of my fellow arriving passengers the great queue for the free station bogs had evidently proved too much and they had taken themselves off for a fit of al fresco cacking in the silence and shadows behind the skateboard park, at the end of Yitzhak Rabin Garden. No clack and hiss of boards in action at that hour. In need of relief myself after the night journey from London, but reluctant to enter an overpriced cafe, I stamped off with my luggage to a railway station where, after swiping a euro from my bank account electronically, a gleaming barrier ushered me, past a spruce attendant, Franco-African or African, into a spotlessly clean convenience.

Four hundred kilometres (250 miles) away at dusk, in the French factory town of Mulhouse, where Peugeot and Citroën cars are assembled and the nation’s other industrial might is remembered, in huge museums, a dusty little square has, for one night only, been magicked into an opera house.

Banks of hot lights preside over stretches of canvas and mysterious arrangements of props, while beatific classical musicians bearing immaculate instruments, serene as sculpted figures peeled from a doorway in a gothic cathedral, thread their way to the orchestra tent through bunches of spectators. Exciting smells of heated metal and make-up spice the air, cut occasionally with a puff of cigarette smoke from the back row, out on the footpath of the Rue du Cerf.

To perfect the evening for me, with my simple, traditional tastes, an audience of excited factory girls would be waiting to see Carmen come strutting out to cheek the world, but these are other people and this is not Bizet.

Andrias Scheuchzeri is an opera I never saw produced before, based on a book I only started on the way over from England. Gliding through the French countryside on the coach this afternoon, charmed by elegant church steeples and lulled by the motion of wind turbine blades, I allowed my mind to drift into the Southern Sea setting of this book, The War With The Salamanders. By a fraction I had slowed down the audio book for the excellent reasons that it was in French and I struggled with some exotic new vocabulary, but this only deepened the sense of slipping below the surface of another existence.

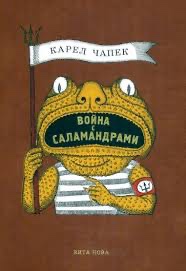

Let me explain a few things without trying too hard to explain the War itself, which would no doubt defeat brilliant minds in sober bodies. Czech author Karel Čapek wrote Válka s Mloky in 1935 (published the following year). Usually rendered in English as War With The Newts, the book has been translated into other European languages like Russian or French as The War With The Salamanders or War With The Salamanders and I just prefer that title. When you realise the creatures in the novel are man-sized, talking and intelligent, it matters even less whether you call them salamanders or newts or even mankeepers, as they still do in rural Ireland, where my parents were from, and where small children were once warned to stay away from pools of water or wells lest a mankeeper dart down their throat and breed inside them until they wasted away.

In this science-fiction novel mankind discovers a handy new humanoid species, the peaceable giant salamander, living – where else? – in the warm waters of the Global South. Humans end up exploiting salamanders to the point of provoking a catastrophic war.

However, the book is much more than a satire of human greed. It is funny in a way which Animal Farm is not and which that earlier great Czech novel, The Good Soldier Švejk by Jaroslav Hašek, is. There are jokes about Hollywood and the world of advertising, and complex, melancholy characters like the sea captain who first discovers the salamanders and charts a channel to watery Hell with his good intentions.

“The sea is vast and the ocean of time has no bounds,” Captain van Toch says early on, before endeavouring to help the salamanders through the kindly introduction of human technology.

“Spit in the sea and it will not rise. Curse your fate and it will not change.”

The captain’s words echoed in my mind all day as I tried to understand what Čapek meant in his book, writing back in 1935 when a new war in Europe looked only a matter of time.

I am sitting on the fat black cushion of a large cantilever chair which was presumably dragged into the square out of a living room in one of the houses to stand in the dust of this Indian Summer Saturday, among its assorted four-legged dining-room friends made of wood. The cushion is big enough to clasp three small, happy French Arab girls, I will note after I get up to stand, later on. My stomach is digesting a recent meal of chicken, chips and orangeade eaten in one of those quaint French street-corner cafes, prepared by a Chinese cook and cheerily served by a Chinese waitress.

In my part of the coach hurtling east this afternoon sat six unrelated Africans – people either from sub-Saharan Africa or with family origins there, five men and a woman, mostly thin. Over seven hours and 25 minutes, the best part of this sunny day, I noticed just one take out food. It was a biscuit or a bar and he nibbled on it, almost furtively. None of the others ate or drank that I could see. My own lunch of cheese and crackers felt generous but was as nothing compared with the hearty, spicy odour of the food unwrapped by a loving couple of happy Ukrainian pensioners or with the cornucopia-like bakery sandwich wolfed down by a young white Frenchman whose fleshy thighs strained to be free of his ripped jeans. An amicable Albanian man, I observed, fed not on food but photos on his smartphone, feasting on pictures of empty rooms with parquet floors in some newly built or renovated house.

Tomorrow when I check out of my comfortable hotel in Strasbourg I will seek out the chambermaid, who turns out to be Afro-French or African, and I will give her a €5 tip “because the room was so nice” and I will be quite startled and moved when she grins and says thanks, as if I have given her a tip of 50 or her first tip.

Today the blades of the wind turbines turned, cogs in a vast machine of green or greener energy production stretching across this land. In the region where I was bound, the Greater East (Grand Est), there turned much greater cogs in the vast nuclear plant of Cattenom and the Strasbourg hydroelectric station, part of a grand plan I will only fully understand some days from now when I go to the Electropolis Museum in Mulhouse and follow its wonderful, winding diorama of French electricity generation. Every time I saw a tram glide past in the cities our coach visited – Dijon, Besançon and finally Mulhouse – I rejoiced in the thought of green or greener energy, in the joy of a cleaner, higher power that salamanders would have never experienced in their deep blue seas.

I thought of the happy men and women, mostly white, often old, usually much wealthier than I, in their green electric trains traversing the railway line between London and Strasbourg. And it hurt a little to think that my coach journey had a higher carbon footprint than theirs though it was a lower one than that left by those who ride in cars and was tiny compared with that of those who fly in planes. I had paid £96.96 for my coach ticket because I had lacked £434 for electric trains and £260 for non-electric planes and though sitting in the British Islands going nowhere would have cost nothing at all, neither to me nor to the environment, I had to see the world again.

“It brings a bit of life to the neighbourhood,” says the goodnatured man perched beside me on a twin cantilever, talking in French, just before the imaginary curtain rises on the back-street opera. He can talk to me in English if I prefer or in Arabic if necessary. From our brief conversation I also know he could talk to me at length about rugby, this autumn when France is hosting the World Cup. But now the opera marches in on us.

Bewildering waves of sound and howls of dialogue rend the warm summer air as the cast march about in the round, to and fro past our improvised seating areas, pursued by their ecstatic director. Here a chain gang of humble salamanders steals the audience’s collective heart, there a captive salamander sits meekly in a booth for all the world to gawp at. Vampiric capitalists circle Captain van Toch. It is wonderful pantomime, if not quite the opera I have been hoping for.

I pick up one of the beautifully produced programmes, free of charge just as the opera itself is free and open to all. At a diplomatically chosen time I hasten into the night, feeling completely unnoticed as I make my way down the empty footpath of Rue de l’Aigle in the direction of the railway station. If I turn back the other way I will come out on the Avenue Aristide Briand with its halal food shops and cafes. If I veer right I will eventually come upon more traditional French shops and cafes among which a billboard is plastered with French nationalist posters. But I have to travel, not eat or drink or work.

On my way I pick up my luggage from an Algerian man I befriended earlier who offered to look after it for me. I look at him again and again I have to tell myself he is not actually native French because he looks to me completely European. I only know he immigrated here because he mentioned it to me himself in passing.

Groups of three or four young French Arab men dot the emptying station, crouching around benches or on staircases this Saturday night, staring. The train to Strasbourg is busier than I expect. Most of my fellow passengers are also young French Arab men – no women – but these are better-dressed than the station-watchers, more like students, ordinary-looking, happy chatty French blokes who only stand out for being ethnically North African in a carriage with few white people aboard. Presumably, of a weekend, they have fewer places to go, and fewer choices of transport, as they take the train from one city to another.

Tomorrow morning I will find myself walking quite by chance behind two teenage French Arab boys along an empty Sunday-morning street from Strasbourg’s railway station area towards the centre. The fatter of the pair carries an empty plastic water bottle which he uses to slap everything he passes, metal railings, sign-posts, bins, quite harmlessly but noisily, marking in sound his passage towards the glories of the medieval city centre at the heart of Europe beyond which lies the German-built university where, I will learn on a visit to a museum that afternoon, scientists once strained to collect data from painstakingly crafted machines to monitor earthquakes for the good of us all in a seismological station which opened in 1900, around the time when France was completing its long conquest of Algeria.

Only when I open the programme on the train leaving Mulhouse do I appreciate how much I missed in the opera performance I left before the final imaginary curtain fell. In my hands is a loving tribute to the hard work and passion of the community theatre which annually produces this “cathartic story”. I discover its vision of enriching lives in a rundown neighbourhood through art, both its creation and its representation, uniting local amateurs with professional outsiders.

“I take part in this project because I love it when music goes where you least expect it,” one artiste is quoted as saying. For another, Andrias Scheuchzeri is a chance to “learn and discover the universe of opera but also to meet people with different horizons”.

I can see the noble ambition of bringing opera to a community where few would otherwise go see it in a theatre, even if they could afford it. The buzz around community art is genuine too and the appeal of this simplified story of injustice is obvious but what would Čapek have made of it? After all, the Czech jester’s rebellious salamanders apparently turn full human and end up following a former corporal in what couldn’t surely be any allusion to Hitler.

Tonight, after crossing the vast station square in Strasbourg, where Africans stand in small groups along the paths, I check into my hotel, drink a beer in my quiet high-rise room and lay me down in a perfectly made bed.